The Great Untold, a new podcast by a Canadian producer and a British media company, debuts with a bang and a unique guest from Panama.

Living in a podcast age

In journalism, the interview has a sense of purity that is almost sacred: there’s the subjects, the interviewees, and the valuable information that they bring forth; there’s the interviewers, the actual journalists or hosts, who do the research and ask the key questions; and then there’s the setting, usually a simple arrangement of a table, microphones and a couple of chairs.

Interviews are great because you get the facts straight from their source. The advent of the internet, blogs and social media have allowed people to share their knowledge of any sorts with a global audience, without filters and in a straightforward manner. What the journalist brings to the table is that keen sense of presenting newsworthy data in an entertaining and informative way.

It’s been at more than a decade since podcasts began. Before, and up until the first decade of the XXI century, we had old school tv journalists such as Larry King or Charlie Rose (Panama’s equivalent was Luz María Noli), expert, no fuss interviewers who could make anyone seem interesting or worth listening to. The fact that their shows ran in big networks on primetime television proves their interest to the overall public, and some of their interviews are now legendary.

But we are now living in the age of Joe Rogan and many others like him. Not journalists per se, they have gathered and audience based on common interests, such as sports or entertainment or philosophies and ideas, so much so that their guests and interviews have had an impact on things like elections or shaping the current zeitgeist.

The comedian, actor and writer Marc Maron is credited as a podcast pioneer, and his show, WTF with Marc Maron, rode this wave until its host and producers decided to call it quits in 2025 after their very successful 16-year run. Part of their decision is based on how the format has become almost ubiquitous. Although they laid the groundwork for its development and growth, both from a production point of view as well as from allowing the audience to appreciate the format itself, it seems fair for them to move on to the next thing and let others take advantage of what they achieved.

There are all kinds of podcasts for all kinds of people. In this sense, podcasts are now like old radio broadcasts that you can listen to while you’re doing your housework, exercising or just having a moment out in front of your laptop during lunch. There is one kind of podcast that seems particularly striking, daring to say what others don’t, and those are one on one interviews with survivors, trauma victims or regular people who have lived through uncommon experiences.

The American photographer Mark Laita’s Soft White Underbelly, as well as Britain’s LADbible videos (not quite podcasts because they show only the guest, but online, long-form interviews nevertheless) have done some amazing work in presenting no holds barred, bare bones Q&A’s with people that Larry King or Charlie Rose wished they could get access to: former addicts of all kinds; people on the fringes, such as sex workers or forensic specialists; and many others whose stories, upon hearing them, beg the question: why isn’t this a film yet?

This current media environment, as well as the desire to do something new and edgy, has led an experienced television and film producer, Nicholas Racz, who has developed shows for networks such as AMC, FX and Fox, to create The Great Untold YouTube podcast. Its first episode, which debuted in mid-September, really delivers. And the reactions to that particular interview, especially in the country and to the people connected to its subject, has been quite telling.

A child of the dictatorship speaks!

During the sixties, seventies and eighties, in Eastern Europe as well as in so-called “third world countries” in Africa, Asia and Latin America, dictatorships, juntas and military regimes were rife. From Ceausescu in Rumania and Saddam in Iraq to Idi Amin in Uganda and Pinochet in Chile, so called “strongmen” took power though coups (and US-CIA support in some cases!) and heralded “social change.” That supposed change came too little or too late, and what was left was tales of abuse of power, as well as the abduction, murder or disappearance of dissenters. This is a common thread in these situations without exception.

The families of those dictators and military personnel in power usually, and with just reason, stay mum and keep to themselves after democracy –or something like it– brought their social yet corrupt dream down. Some have had a heavy burden put on their lives because of their relative’s actions. Some leave their countries never to come back. Those who do speak up are the survivors, the sufferers of those abuses, or the family members who honor their memories and sacrifices.

In Panama we had Omar Torrijos, a divisive figure even now as the country revisits its recent history. His main mission, after coming to power via coup in 1968, was to achieve Panama’s total sovereignty by making a deal with the United States to leave the canal they had built and run for over 80 years to his country folk. This also included giving back the area of the “canal zone” where the military and civilian personnel that run the operation lived, an ideal colonial enclave if there ever was one. The thing is that Torrijos did achieve this in his lifetime, after a massive international (and even national) lobby campaign. He is quoted, unlike many of his strongman colleagues, as saying that after signing the Torrijos-Carter treaties with the US in 1977 he would retire and read. But, alas, he was killed on a rainy day in 1980 while flying on a small plane to his private hideout in Panama’s central mountains. In came the infamous Noriega.

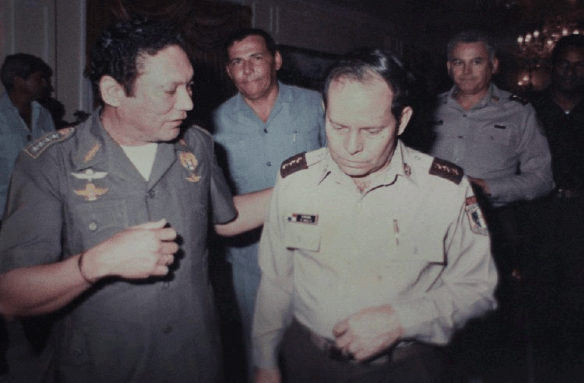

Manuel Antonio (Tony) Noriega was Torrijos’ intelligence man, so much so that he ended up becoming a CIA spy as well. He did the dirty work, to put it mildly, things that now are referred to as “black ops.” When Torrijos died unexpectedly Noriega rose to power through the ranks, and through cunning actions he made sure that he clung on to that power. As the mid-eighties rolled in, and in complete control of the country, the now general Noriega started dealing with Colombian drug cartels, with Pablo Escobar and company, Panama being Colombia’s neighbor and a perfect place to either ship or fly drugs to North America.

One of Noriega’s right-hand officers was colonel Roberto Díaz Herrera, an also shortish man with a military education and all of the bravado that came with it. Yet, for reasons that he has disclosed publicly, Díaz Herrera became the first high-ranking officer to publicly denounce Noriega in 1987, renouncing his command and holding marathon-like press conferences in his home to tell the press about the general’s illicit activities and disregard for Panama’s democratic future.

It was this whistle blower’s first son, Roberto Díaz Tapiero, who became Nicholas Racz’s first guest in his new podcast, almost forty years after Noriega and his father’s regime came crumbling down through a US military invasion of Panama in 1989.

The TV producer got connected to the Panamanian “son of the regime” through a mutual friend. Once Racz heard what Roberto Díaz Tapiero had to say, what he had lived through and survived, he asked him to be on The Great Untold’s debut episode. Coincidentally, Roberto had been planning to pen his autobiography, a no-holds-barred, scorched earth, tell-all autobiography in which he would exorcise the family ghosts and heal his very heavy personal traumas.

The almost 120-minute interview, which you can watch here, is riveting, and also heartbreaking and surprising. It shows a fresh looking, middle-aged Latino man (Roberto has dark curly hair with grey specks, wears a button-down shirt and speaks in a neutral American accented English) consciously coming to terms with a family past that you wouldn’t wish on anyone.

A first revelation is him losing his virginity at age 12 with a prostitute, egged on by one of his dad’s cronies. This has been a common occurrence in countries where a macho male identity prevails, yet few men speak out about it as a traumatic experience years later. Because, after all, it is a kind of sexual child abuse. He also discloses that he was used to handling guns since his early teens, being able to shoot an uzi machine gun at 15. Even though this might be many-a-kid’s fantasy all over the world, we now know that no child should hold any kind of military grade weaponry just to become “a real man” in the future.

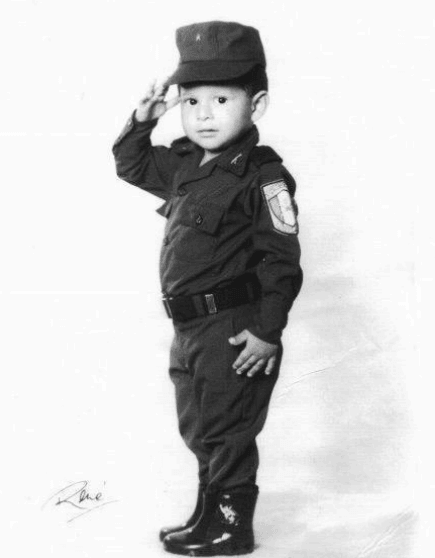

A child of the regime: Roberto Díaz Tapiero as a young boy in full Fuerzas de Defensa de Panamá uniform.

When colonel Díaz denounced Noriega his home became a stronghold, with loyalists, family members and friends staying over to protect the now enemy family. During the interview the closeness of the Díaz and Noriega families is talked about, with uncle Tony (the dictator) spoken of as a close family friend, dad’s boss and a caring father to his daughters. The fact that both military men had only daughters and were competing to see who would have a son first, a sort of scion of the regime, meant that upon Roberto’s birth he had that notion drilled into him: he would have to be an extra tough man to follow up on his dad’s and Uncle Tony’s one-two steps.

General Manuel Noriega and colonel Roberto Díaz Herrera in the mid eighties at the apex of their power.

The fact that a straight, middle age Latino man can talk about “toxic masculinity” and “trauma” is, quite frankly, one of this interview’s main feats. Latin American men and Latino culture are still quite sexist and male-centered, so any kind of personal development of this psychological and socio-cultural sort is more than welcome. There may just be hope for the future.

Racz is a good interviewer in that he asks key questions, doesn’t talk over the guest and appears sympathetic and understanding. Díaz Tapiero also provides good content, and at moments he still seems shaken by what he is saying and what happened to him. They both laugh at certain points to create some lightness, but one can imagine some viewers gasping in disbelief.

Canadian producer and host Nicholas Racz.

Other allegations (or declarations) of abuse are made. At 17, Díaz Tapiero saw a man being tortured in his back yard and was told to participate. When Noriega’s people apprehended the Díaz family, he was beaten himself and thought that his father would be executed in front of them. In later years, both as a teenager living in the US and Venezuela, then as an adult, all of these experiences created a very angry man, with commitment and jealousy issues as well as a very violent temper and a proclivity to violence.

Díaz Tapiero’s autobiography is not his first book: Roberto has actually penned five children’s books! All it took for him to start on his road to mental recovery was surfing and having kids. So, after living in California and Hawaii where surfing is a favorite sport, and while also beginning to work on himself through therapy (he was diagnosed with complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder from childhood), he wrote books about surf and skate safety for kids. When he moved back to Panama more than a decade ago, he also wrote a bilingual book (in Spanish and English) titled My Panamanian Pride, about local school kids learning about how to protect the environment and reduce overall pollution.

Veiled memories

The Panamanian national anthem has a very peculiar line that, when translated, comes out a bit like this: “It is precise to cover the Calvary and the cross with a veil of the past,” meaning “let’s try to forget all this suffering and strife and carry on.” Revisiting history, and making amends with it, is a tall order. Perhaps only the Germans have taken this on head first, for reasons that might be obvious for them and to the world, while other nations, from the imperialistic powers to the “underdeveloped” dictatorships, still shy away from it. The United States leads the way in this sort of hypocrisy.

When Panama’s “legacy media” and journalists got an exclusive about Díaz Tapiero’s statements in Racz’s new podcast, the response was slow, lukewarm and even disdainful. Some news editors would not run it because the subject is an unknown, i.e. not a political, social or business player, while others just dismissed it. The journalists who did run with the story mostly focused on the Noriega-Díaz family dynamic during the dictatorship’s final years. None of them actually watched the podcast in preparation, or talked about the podcast itself, a contemporary format that could now become a prime source of newsworthy information, as this has proven.

When other Panamanians where presented with the link to the YouTube episode, some of them of Roberto’s generation who remember his father and what he did, were also dubious of him doing the podcast, or taking what he said with a huge grain of salt considering that, yes, his father was part of an oppressive regime where few hands come out clean. An educated economist and writer of his age group, who is also gay and married in Europe, said he would have to watch it in installments because people like Roberto were the ones who abused and bullied him as a kid. A fifty something market analyst, who is also into psychology and healing, could perceive a note of dissociation in Roberto’s eyes when he spoke, a coping mechanism for heavy trauma.

Panamanian contemporary media has podcasts, but not so much about history or dealing with complicated personal issues. Yes, local newspapers, TV news and radio interview all kinds of people, but why waste the little time and space that they now have (the internet has decimated these media companies) for their daily news on this foreign podcast with this man’s problems, a person who despite his hardships grew up in relative affluent environment?

The fact is that The Great Untold’s first interview is good content. In two weeks it has gathered around 700 views and 59 subscribers, not a massive viral hit, but just another new, online show finding its audience, and one that is sure to gain some traction as future episodes come out or “drop.”

The Panamanians overall reaction to Roberto Díaz Tapiero’s bold statements and personal growth prove that this type of content can strike a nerve, and some people have their reasons to doubt his intentions and motivations. Perhaps once his autobiography is published he would be taken more seriously in his own country, as his personal Calvary might inspire others to heal and come to terms with their past.

For Nicholas Racz and his new podcast, well, he’s just getting started. As he works on his second episode he strives to deliver what he promised in a formal press release for the show: “The Great Untold featuresremarkable true stories that might otherwise be lost to history. These are first-hand accounts of remarkable events—some controversial, some astonishing—that deserve to be documented, preserved, and shared with the world. This channel is an archive of human experience, shedding light on critical narratives that mainstream media often overlooks.”